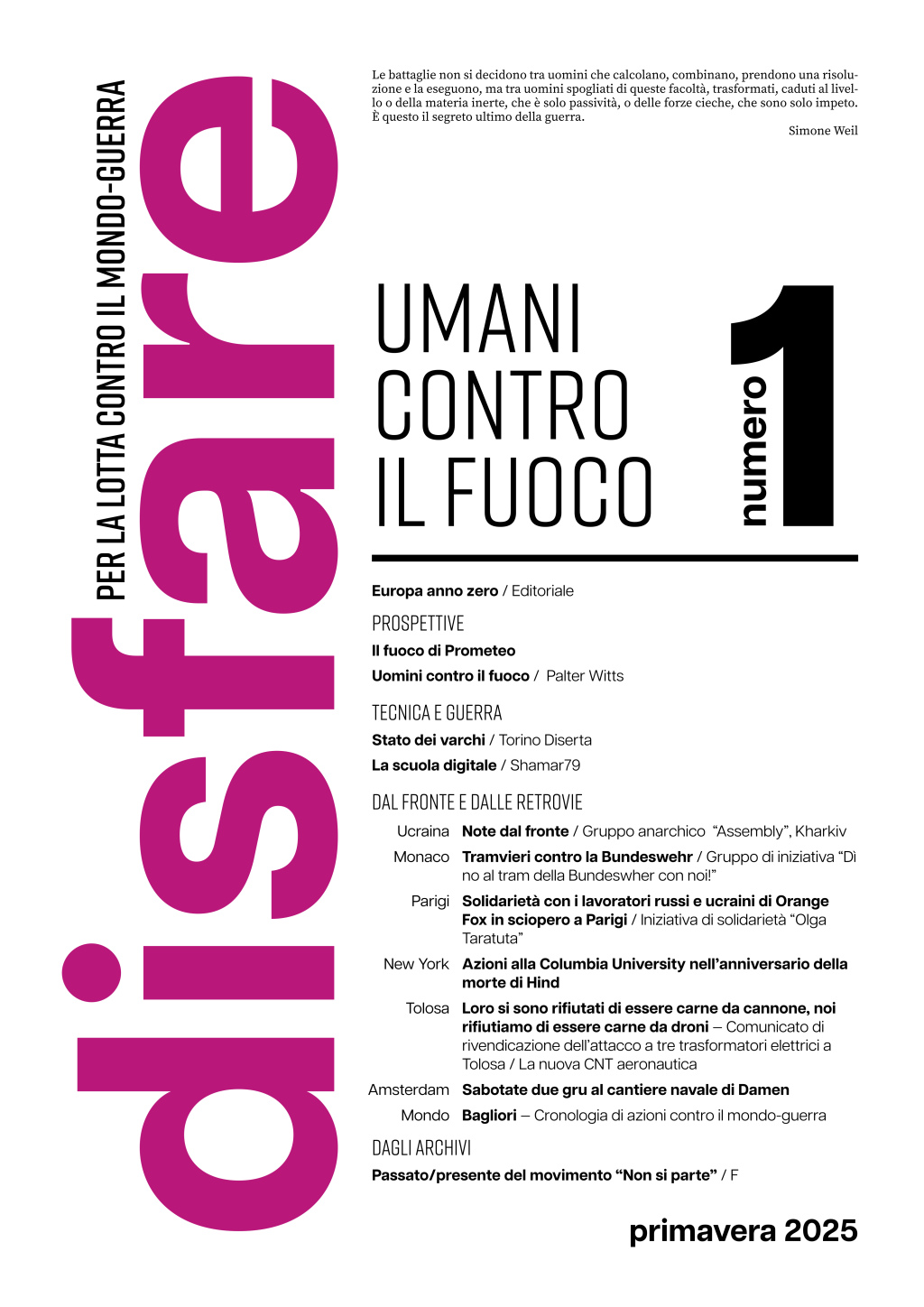

È uscito il primo numero di “disfare – per la lotta contro il mondo-guerra”

Riceviamo e diffondiamo:

Per richiesta di copie / To request copies / pour demander des exemplaires: disfare@autistici.org

Scarica il pdf dell’anteprima / Download the preview in pdf / pour télécharger le pdf de l’aperçu: disfare_1_anteprima

Scarica la versione inglese dell’editoriale / Download the english version of the editorial: disfare_1_editorial_ENG

Scarica la versione francese dell’editoriale / pour télécharger la version française de l’éditorial: disfare_1_editorial_FR

- 36 pagine, 3 euro a copia, 2 euro per i distributori (dalle 3 copie in su)

- 36 pages, 3 euros per copy, 2 euros for distributors (from 3 copies upwards)

- 36 pages, 3 euros par exemplaire, 2 euros pour les distributeurs (à partir de 3 exemplaires)

[english and french below]

Editoriale

Europa anno zero

Mentre, nello Studio Ovale della Casa Bianca, urla in faccia a Zelensky: «Vai in giro e costringi i coscritti in prima linea perché hai problemi di uomini», JD Vance non fa altro che svelare al mondo intero ciò che per tre anni è stato nascosto dalla propaganda di guerra atlantica, e che viene adesso rinfacciato – strumentalmente e non certo per motivazioni etiche – dal nuovo corso USA, di fronte ad una guerra evidentemente persa e ormai sfacciatamente scaricata sulla popolazione europea. Un’Europa la cui classe dirigente – riaffermando la difesa fino all’ultimo ucraino con la retorica della “pace giusta” – annuncia con patriottismo democratico scellerati piani di riarmo e deterrenza nucleare.

La guerra è l’orizzonte storico terribile del nostro tempo.

In Svezia e Norvegia vengono distribuiti opuscoli e si allargano i cimiteri per predisporre la popolazione all’eventualità di una guerra con la Russia; Von der Leyen dichiara di volere «la pace attraverso la forza»; Macron propone di estendere la force de frappe francese all’Europa; in Lombardia si dispone l’ampliamento delle scorte di iodio nell’eventualità di attacco nucleare; la NATO promuove la mobilitazione della società civile dei paesi alleati nell’Indopacifico per preparare un conflitto con la Cina; l’esercito italiano si prepara ad arruolare quarantamila soldati in più.

In un quadro di interdipendenza tecnologica e finanziaria fra Cina e Stati Uniti, con l’elezione di Trump viene alla luce lo scontro in atto da anni tra la fazione globalista e quella sovranista delle classi dirigenti occidentali. Per sommi capi, la prima è decisa a uno scontro diretto e a qualsiasi costo con la Russia, la seconda favorevole a un’intesa col Cremlino per puntare, nel giro di alcuni anni, direttamente contro la Cina, ma entrambe convergono su un punto preciso: il riarmo europeo (peraltro deciso e annunciato molto tempo prima del ritorno di re Donald). Un gioco di specchi e provocazioni che, mentre potrebbe sfociare da un giorno all’altro nell’annientamento nucleare dell’umanità intera, trasformerà l’Europa, se non in un cumulo di macerie radioattive, in una fortezza blindata e militarizzata, dominata da un’economia di guerra che assorbirà tutte le risorse e le energie sociali.

La guerra del nostro secolo è ibrida, totale, asimmetrica, civile. Il suo campo di battaglia è ovunque.

La guerra del XXI secolo è una guerra senza limiti, che assume forme varie e pervasive. Si snoda tra i flussi energetici, prende la forma di attentati e sabotaggi di Stato, incorpora pienamente il denaro, i mezzi di informazione e i social network. La centralità assunta dalla tecnologia e dallo sviluppo scientifico si riverbera in ogni ambito del conflitto guerreggiato, attraverso droni, applicazioni che coinvolgono la popolazione nei servizi di intelligence (ad esempio per segnalare le posizioni delle unità nemiche), così come con la rivoluzione dell’intelligenza artificiale nelle dottrine militari, che ha un peso e delle conseguenze paragonabili all’invenzione del nucleare. Se l’IA e le tecnologie digitali sono fondamentali per fare la guerra, la ricerca del primato su questi dispositivi alimenta la competizione su scala internazionale per il saccheggio di materie prime e la vampirizzazione energetica. Le ipotesi di “deterrenza batteriologica” e la valenza apertamente militare dei bio-laboratori fanno coincidere guerra guerreggiata e guerra al vivente.

Non per questo vengono meno forme “tradizionali” e sanguinose, riemergenti nei fronti di una guerra mondiale che per ora sarà anche «a pezzi», ma che si delinea sempre più chiaramente come prodotto della crisi dell’egemonia globale statunitense e contesa con i suoi sfidanti, in particolare la Cina. Sul fronte ucraino, la leva di massa e la guerra di posizione ci ricordano quanto avveniva durante la Prima Guerra Mondiale. Sul fronte mediorientale, dove per gli USA mantenere saldo il colonialismo d’insediamento israeliano – sorto come avamposto degli interessi occidentali – significa cercare di preservare il proprio predominio sulla regione, il genocidio sionista a Gaza e in Cisgiordania riporta all’attualità quanto avvenne durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale. In nessun caso si tratta però di un ritorno del Novecento, bensì del reciproco alimentarsi di progresso tecnico e mobilitazione generale nella guerra totale del XXI secolo.

Il potenziamento della tecnica è oggi l’orizzonte centrale per le forze che si contendono il dominio del mondo.

Con un rovesciamento tra il concetto di mezzo e quello di fine, la tecnica guidata dalla scienza moderna si afferma secondo una propria logica. Il ruolo del sistema satellitare Starlink di Elon Musk – impostosi con la guerra in Ucraina – dà la misura di un protagonismo inedito delle multinazionali dell’high-tech, ma, come in altre fasi della rivoluzione industriale, non viene meno il ruolo dello Stato, che anzi assume una rinnovata centralità. Non è un caso che il Progetto Stargate della nuova amministrazione USA – 500 miliardi per lo sviluppo dell’IA – sia stato paragonato al Progetto Manhattan, quello che portò ai bombardamenti atomici di Hiroshima e Nagasaki.

La natura automatizzata del genocidio a Gaza appare come la sperimentazione sui “selvaggi delle colonie” di quello che rischia di accadere ai civilizzati stessi, allo stesso modo in cui il genocidio degli Herero in Namibia da parte del colonialismo tedesco (e l’insieme dei genocidi commessi dalle altre potenze coloniali) precedette e preparò l’attività dei campi di sterminio durante il nazismo. E mentre diventa sempre più chiaro come nell’organizzazione del mondo-guerra vi sia un’umanità eccedente di cui si può fare a meno e che va gestita o eliminata, si sta sdoganando l’idea che si possa fare a meno dell’umanità in quanto tale (come sostenuto apertamente da alcune correnti tecnocratiche tutt’altro che lontane dalle stanze dei bottoni).

La guerra è prima di tutto un fatto di politica interna – e il più atroce di tutti.

Così metteva in guardia Simone Weil, ventiquattrenne, nelle sue Riflessioni sulla guerra (1933), rispetto all’errore di considerare la guerra come un fatto di politica estera. Se i fatti drammatici a cui assistiamo ogni giorno in diretta streaming rischiano di apparirci distanti, la guerra è più vicina di quanto inconsciamente ci auguriamo.

A pochi passi da noi stanno infatti le sue molteplici basi materiali – dai centri decisionali alle fabbriche d’armi e munizioni, passando per snodi logistici che sono parti integranti della logistica militare e un sistema universitario che fa da laboratorio all’industria bellica –, sempre più nutrite da imponenti piani di riarmo. E nel mondo datificato e digitalizzato i confini fra civile e militare sono continuamente superati in entrambi i sensi: una app che oggi viene usata per profilarci come consumatori, pazienti sanitari o “cittadini digitali”, può servire, altrove come qui, per mettere al bando, arruolare, o eliminare una parte di umanità considerata nemica o inutile, mentre i dati che produciamo tutti i giorni sono direttamente al servizio della sorveglianza e degli eserciti.

Se è vero che la guerra parte da qui, è altrettanto vero che la guerra torna indietro. Ritorna come necessità di “pacificare” le retrovie, militarizzandole: la sperimentazione delle “Zone Rosse” dopo Capodanno, il tentativo di varare un codice da legge marziale col Pacchetto Sicurezza (firmato anche dal ministro della Difesa), l’estensione del “modello Caivano” ad altre periferie. Sul piano interno, sono numerose le conseguenze a cascata del conflitto tra gli Stati fatte pagare alle classi dominate – aumento delle bollette, precarizzazione ulteriore del lavoro, fine di quel che rimane del cosiddetto “Stato sociale” – giustificate dalle necessità del riarmo e della difesa nazionale e Europea, con l’utilizzo costante dell’emergenzialità e la militarizzazione delle emergenze. È ciò che abbiamo ampiamente vissuto durante il “periodo pandemico”, in cui la guerra al virus ha predisposto il terreno per la guerra attuale con la sperimentazione su larga scala di una mobilitazione generale.

La guerra totale è contemporaneamente guerra civile globale.

Le condizioni di questa guerra civile sono ampiamente in essere anche alle nostre latitudini, come più d’uno ha affermato già nel secolo scorso. Il venir meno di collanti ideologici, la conflittualità intestina allo Stato e pure alle classi frantumate, sono sintomi che la barbarie non è qualcosa di lontano, ma si dispiega anche all’interno delle mura erette dalla “civiltà” e dal “progresso”. Basti pensare a quanto accade nelle periferie come riflesso della “guerra tra poveri” – italiani contro stranieri, disoccupati contro lavoratori “del nero”, piccoli esercenti autorizzati contro abusivi, regolari contro clandestini, abitanti delle case popolari contro occupanti, cittadini contro rom, antagonisti contro “maranza”… Se poi ci spostiamo nel Regno Unito, vediamo tornare né più né meno che i pogrom (con migranti e islamici al posto degli ebrei e dei rom). Se le insurrezioni e le rivoluzioni moderne sono sempre delle guerre civili, i due termini non coincidono. Oggi siamo precisamente in presenza di una guerra civile ubiqua e orizzontale in assenza di guerra sociale.

Capita però che talvolta il conflitto si esprima verticalmente, come nelle sommosse di George Floyd e poi, con una composizione socialmente diversa, e per certi aspetti opposta, nell’assalto a Capitol Hill (USA, 2020 e 2021: prima proletari di tutti i colori contro padroni e istituzioni, e in particolare contro la polizia; poi una miscellanea di classi, ma tendenzialmente plebee e bianche, contro l’elezione di Biden); negli scontri dei popoli nativi contro il marco temporal dell’agroindustria (Brasile, 2023); nelle sommosse delle banlieues francesi (dal 2005 alle più recenti “rivolte di Nahel”) e, alle nostre latitudini, nelle accese manifestazioni antipoliziesche dopo l’assassinio di Ramy Elgaml a Milano da parte dei carabinieri.

I fenomeni di disintegrazione sociale rappresentano in ogni caso una minaccia per l’ordine costituito, a cui lo Stato risponde in maniera autoritaria, in modo del tutto trasversale alle tassonomie di governo formali (democrazia vs. autocrazia), senza mediazioni se non quelle offerte dal progresso tecnico. Basti pensare alla digitalizzazione e biometrizzazione delle identità legali, tramite cui l’identità civile diventa indistinguibile da un dispositivo di sorveglianza automatizzato. Oggi il “cittadino” che si rivolta o non obbedisce è sempre più meccanicamente “messo al bando”.

Prendere atto della tendenza alla guerra non significa accettarne l’inevitabilità.

Nonostante la religione dell’ineluttabilità sia il motore del nostro tempo, alcuni segnali sembrano incrinarla. In Ucraina, dopo la sbornia nazionalista, il sostegno alla guerra ha lasciato il posto a forme di renitenza, diserzione e non-collaborazione di massa che pesano non poco sulle sorti di quel conflitto e lasciano intravedere un possibile crollo del fronte occidentale. Nel frattempo, il genocidio a Gaza ha alimentato un movimento globale vasto e articolato che, grazie ad alcune testarde minoranze, ha riscoperto forme d’azione diretta e ha portato l’intifada nei campus statunitensi, facendosi carico di dire il non-detto, cioè il fondamento bellico e genocida del capitalismo occidentale. L’estensione della guerra a tutti gli ambiti della società moltiplica le opportunità di ammutinamento e sabotaggio, offrendo alla variabile umana inedite occasioni di inceppare la macchina mortifera.

La propaganda di guerra – paradossalmente – ha avuto invece presa su alcune minoranze della minoranza antagonista, arrivate a esprimere sostegno a una sedicente, e inesistente, resistenza ucraina, e a esitare, nel contempo, a sostenere la resistenza palestinese, con la totale incapacità di distinguere tra un’ondata nazionalista fomentata e armata dalla NATO (e con autentici nazisti in prima fila, tra Parlamento, squadroni della morte, esercito, polizia, Guardia Nazionale) e una resistenza anticoloniale contro un colonialismo d’insediamento ancora in corso. Se i socialisti parlamentari di un tempo votarono i crediti di guerra, i loro ridicoli e corrotti eredi “progressisti”, dopo un secolo di collaborazionismo di classe, sostengono il piano di riarmo “ReArm Europe” e indicono piazze guerrafondaie “per la libertà”, volte unicamente a sostenere la prosecuzione del massacro in corso in Ucraina.

A centodieci anni dall’entrata in guerra dell’Italia nel Primo Massacro Mondiale e a ottant’anni dalla fine del Secondo sul suolo europeo, sono la storia dell’antimilitarismo rivoluzionario e ancor più quella di chi lo ha abbandonato abbracciando la causa della “guerra giusta” di turno a illuminare tragicamente la strada da percorrere. L’unico modo di sottrarsi a guerre fratricide è assumere la logica del disfattismo e le sue implicazioni, ovvero adoperarsi per la rovina della parte capitalista che ti vuole arruolare e intruppare, e l’unico modo per sottrarre il disfattismo dall’arruolamento da parte del campo capitalista avverso è la logica dell’internazionalismo: quella con la quale ogni sfruttato vede il proprio nemico nel padronato di casa propria, solidarizzando con i propri fratelli e sorelle dall’altro lato del fronte.

¯¯¯

Con questo sguardo sul mondo nasce disfare, bollettino periodico in parte dedicato ad affrontare nodi cruciali per interpretare il fosco orizzonte in cui agiamo, in parte a dare diffusione di testi contro la guerra totale, per lo più inediti in lingua italiana, provenienti dai vari fronti e retrovie del mondo e anche dal passato.

Il bollettino uscirà in quattro numeri annuali, un ritmo oltremodo lento per tenere il passo vertiginoso dell’attualità, ma che ci sembra – oltre che compatibile con le nostre energie – adatto al cristallizzarsi di un pensiero che provi ad avventurarsi oltre la superficie. Ci affidiamo a uno strumento cartaceo, senza escludere che possa essere affiancato da altri mezzi, convinti che nella dimensione digitale tutto sfreccia e poco o nulla si posa, rumore di fondo che non ha più importanza di qualsiasi altro rumore.

Di fronte all’accelerazione di eventi di portata storica che stiamo vivendo, ci sembra utile dotarci di una pubblicazione che possa fornire uno spazio di discussione e in cui possano dialogare fra loro esperienze di lotta e analisi, anche geograficamente lontane e magari divergenti tra di loro, con il desiderio che questo possa stimolare pensiero e azione. Per questo invitiamo chi ci legge a contribuire con testi, grafiche, segnalazioni, critiche, diffusione. Nella speranza che l’accelerazione di questi tempi bui non ci trovi del tutto impreparati.

///

Editorial

Europe, year zero

In the Oval Office of the White House, while he shouts in Zelensky’s face “You guys are going around and forcing conscripts to the front lines because you have manpower problems,” JD Vance is merely revealing to the whole world what has been hidden for three years by the Atlantic war propaganda, and is now being held up to the world – instrumentally and certainly not on ethical grounds – by the new U.S. course, in front of a war that has evidently been lost and is now shamelessly dumped on the European populations. A Europe whose ruling class – reaffirming the need to defend Ukraine to the last Ukrainian with the rhetoric of a “just peace” – announces with democratic patriotism heinous plans for rearmament and nuclear deterrence.

War is the terrible historical horizon of our time.

In Sweden and Norway, governmental pamphlets and the expansion of cemeteries prepare people for the possibility of war with Russia; Von der Leyen declares that she wants “peace through force”; Macron proposes extending the French force de frappe to Europe; Lombardia [region of northern Italy, translator’s note], is increasing its iodine stocks in the event of a nuclear attack; NATO promotes the mobilization of civil society of allied countries in the Indo-Pacific to prepare for a conflict with China; the Italian army prepares to enlist forty thousand more soldiers.

Against the backdrop of technological and financial interdependence between China and the United States, the election of Trump brings to light the years-long clash between the globalist and sovereignist factions of the Western ruling classes. In a nutshell, the former is bent on a direct confrontation at any cost with Russia, the latter is in favor of coming to terms with the Kremlin to aim its efforts, within a few years, directly against China. Both factions, however, converge on a specific point: European rearmament (which was decided and announced long before King Donald’s return). A game of mirrors and provocations that, while it could result in the nuclear annihilation of all humanity any day now, will turn Europe, if not into a pile of radioactive rubble, into an armored and militarized fortress, dominated by a war economy that will absorb all energies and social resources.

The warfare of our century is hybrid, full-scale, asymmetric, civil. Its battlefield is everywhere.

The war of the 21st century is a war without limits which takes on varied and pervasive forms. It unfolds through energy flows, takes the form of assassinations and sabotages carried out by State actors, and fully incorporates money, media, and social networks. The centrality assumed by technology and scientific development reverberates in every sphere of the war, through drones, apps which engage the population in intelligence services (e.g., to signal the positions of enemy units), as well as with the artificial intelligence revolution in military doctrines, which has a weight and consequences comparable to the invention of nuclear power. While AI and digital systems are fundamental to military operations, the quest for primacy over these technologies fuels competition on an international scale for the plunder of raw materials and the control of energy resources. At the same time, hypotheses of “bacteriological deterrence” and the overtly military role of bio-laboratories make warfare coincide with war against the living.

But “traditional” and bloody forms of warfare are not disappearing. Rather, they are re-emerging on the fronts of a world war that, while it may be “piecemeal” for now, is clearly a product of the crisis of U.S. global hegemony and U.S. contention with its challengers, particularly China. On the Ukrainian front, mass conscription and positional warfare are reminiscent of what happened during World War I. On the Middle Eastern front, where the U.S. is defending Israeli settler colonialism – which arose as an outpost of Western interests – in an effort to preserve its own dominance over the region, the Zionist genocide in Gaza and in the West Bank brings back what happened during World War II. In no case, however, is it a return of the twentieth century, but rather the mutual reinforcement of technical progress and general mobilization into the total war of the twenty-first century.

The increase of technological power is now the principal domain for the forces competing for world domination.

With a reversal between the concepts of means and ends, technology driven by modern science establishes itself according to its own logic. The role which Starlink, Elon Musk’s satellite system, acquired with the war in Ukraine is indicative of an unprecedented prominence of high-tech multinational companies. But, as in other phases of the industrial revolution, the role of the State is not diminished; on the contrary, the State takes on a renewed centrality. It is no accident that the new U.S. administration’s Stargate Project – 500 billion for AI development – has been compared to the Manhattan Project, which led to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The automated nature of the genocide in Gaza appears to be the experimentation on the “savages of the colonies” of what is likely to happen to the civilized themselves, in the same way that the genocide of the Hereros in Namibia by German colonialism (and the set of genocides committed by other colonial powers) preceded and prepared for the death camps of Nazism. While it becomes increasingly clear that in the organization of the war-world there is an excess humanity which is not necessary and must be managed or eliminated, the idea that humanity as such can be replaced is increasingly being legitimized (as openly advocated by some technocratic currents not far from the control rooms).

War is first and foremost a matter of domestic politics – and the most heinous of all.

With these words Simone Weil, aged 24, in her Reflections on War (1933), warned against the mistake of viewing war as a foreign policy matter. Although the dramatic events we witness every day in live streaming may feel distant from us, war is closer than we unconsciously hope.

The material infrastructures of war, in fact – increasingly nurtured by massive rearmament plans – are often just a stone’s throw away from us: from decision-making centers to weapons and ammunition factories, to logistics hubs that are integral parts of military logistics and to the academic system that serves as a laboratory for the war industry. And in the data-driven and digitized world, the boundaries between civilian and military are constantly surpassed in both directions: a smartphone app that is used today to profile us as consumers, medical patients, or “digital citizens” may serve, elsewhere as well as here, to ban, enlist, or eliminate a part of humanity considered to be threatening or useless, while the data we produce every day is directly at the service of surveillance and armies.

If it is true that war starts here, it is equally true that war comes back. It comes back as a need to “pacify” the zones behind the front lines by militarizing them: the experimentation of “red zones” after New Year’s Eve [since December 2024, several major Italian cities are deploying “red zones”, from which the police can arbitrarily remove anyone considered “dangerous”, n/t], the attempt to enact a martial law code with the “security package” [a set of repressive laws proposed by the current Italian government which targets workers’ struggles and dissent, increases police powers and lengthens jail sanctions on a number of “crimes”, as well as introducing new felonies, n/t] (also signed by the Minister of Defense), the extension of the “Caivano model” to other cities [a gang rape committed in 2023 in Caivano (Naples) was used by the Italian government as a justification to introduce new local repressive measures, a “model” which is now being extended to other metropolitan areas, n/t]. Domestically, there are numerous cascading consequences of the conflict between States whose costs are pushed onto the dominated classes – rising bills, further precarization of labor, the end of what remains of the so-called “welfare state.” These costs are justified by the needs of national and European rearmament and defense, with the constant use of emergencyism and the militarization of emergencies. This is what we widely experienced during the “pandemic” period, when the war on the virus, with its large-scale experimentation of general mobilization, set the stage for the current war.

Total war is simultaneously global civil war.

The conditions of this civil war are largely in place at our latitudes as well, as has been noted multiple times already in the last century. The breakdown of ideological glues, the conflict within the State and even within the fractured classes are symptoms that barbarism is not something far away, but also unfolds within the walls erected by “civilization” and “progress.” Just think of what is happening in the banlieues as a reflection of the “war between the poor” – Italians versus foreigners, unemployed versus illegal workers, licensed shopkeepers versus unauthorized sellers, legal versus illegal migrants, public housing residents versus squatters, citizens versus Roma, antagonists versus “maranza” [slang term indicating youth groups especially of the outer city, n/t]… If we move to the UK, we see the return of nothing other than pogroms (with migrants and Islamists instead of Jews and Roma). While modern insurrections and revolutions are always civil wars, the two terms do not coincide. Today we are precisely in the presence of ubiquitous and horizontal civil war in the absence of social war.

It happens, however, that sometimes the conflict is expressed vertically, as in the George Floyd riots and then, with a socially different, and in some respects opposite composition, in the assault on Capitol Hill (U.S., 2020 and 2021: first proletarians of all colors against masters and institutions, and in particular against the police; then a mixture of classes, but mostly plebeian and white, against the election of Biden); in the clashes of native peoples against the agro-industry’s marco temporal (Brazil, 2023); in the riots in the French banlieues (from 2005 to the most recent “Nahel riots”) and, at our latitudes, in the heated anti-police demonstrations after the murder of Ramy Elgaml in Milano by the Carabinieri [Italian military body with policing role, n/t].

In any case, the phenomena of social disintegration represent a threat to the established order to which the state responds in an authoritarian manner, regardless of the formal taxonomies of government (democracy vs. autocracy) and without mediations other than those offered by technical progress. For example, through the digitization and biometrization of legal identities, civilian identity becomes indistinguishable from an automated surveillance device. Today the “citizen” who revolts or fails to obey is increasingly “banned” in a mechanical way.

To acknowledge the trend toward war is not to accept its inevitability.

Although the religion of inevitability is the driving force of our time, some signs seem to undermine it. In Ukraine, after the nationalist fever, support for the war has given way to forms of mass refusal, desertion and non-cooperation that weigh in no small measure on the fate of that conflict and hint at a possible collapse of the Western front. Meanwhile, the genocide in Gaza has fueled a vast and articulate global movement that, thanks to a few stubborn minorities, has rediscovered forms of direct action and brought the intifada to U.S. campuses, taking it upon itself to say the unspoken: the warmongering and genocidal foundation of Western capitalism. The extension of war to all spheres of society multiplies opportunities for mutiny and sabotage, giving the “human variant” unprecedented opportunities to jam the deadly machine.

Instead, war propaganda – paradoxically – has had a grip on some of the antagonistic minority, who have gone so far as to express support for a self-proclaimed, and nonexistent, Ukrainian resistance while hesitating to support the Palestinian resistance, with a total inability to distinguish between a nationalist wave fomented and armed by NATO (and with genuine Nazis in its front rows, in parliament, death squads, army, police, and National Guard) and an anti-colonial resistance against an ongoing settler colonial project. If the parliamentary socialists of yesteryear voted for war credits, their ridiculous and corrupt “progressive” heirs, after a century of class collaborationism, support the “ReArm Europe” rearmament plan and call for warmongering demonstrations “for freedom,” aimed solely at supporting the continuation of the massacre in Ukraine [the reference is to the pro-European rallies of March 15th held in Rome and in other Italian cities, n/t].

One hundred and ten years after Italy entered the First World Massacre and eighty years after the end of the Second, it is the history of revolutionary anti-militarism and even more so that of those who abandoned it by embracing the cause of a “just war” that tragically illuminates the way forward. The only way to evade fratricidal wars is to take on the logic of defeatism and its implications, that is, to work for the ruin of the capitalist side that wants to enlist and entrench you. And the only way to prevent defeatism from working for the opposing capitalist camp is the logic of internationalism: the one by which every exploited person sees his or her enemy in their “own” ruling class, solidarizing with his or her brothers and sisters on the other side of front.

—

This is the perspective on the world at the core of the project of disfare, a periodical bulletin partly dedicated to addressing matters which are crucial for interpreting the bleak horizon in which we act, and partly to circulating texts against the total war, mostly unpublished in Italian, from the world’s various fronts and from the past.

The bulletin will come out in four annual issues, an exceedingly slow pace for keeping up with the dizzying pace of current events, but one that seems better suited for trying to push our thinking beyond the surface – as well as compatible with our limited resources. We rely on paper, not excluding that it may be accompanied by other tools in the future, because we are convinced that in the digital dimension everything dashes past and little or nothing settles, background noise that is not more important than any other noise.

In the face of the acceleration of events of historical significance that we are currently witnessing, we find it useful to equip ourselves with a publication that can offer a space for discussion and in which experiences of struggle and analysis, even geographically distant and perhaps divergent from each other, can come together and enter a dialogue, with the desire that this may stimulate thought and action. Therefore, we invite those who read us to contribute with texts, illustrations, reports, criticism, distribution. In the hope that the escalation of these dark times will not find us entirely unprepared.

///

Éditorial

Europe année zéro.

Tandis que, dans le bureau ovale de la Maison Blanche, il crie à Zelensky : « En ce moment même, vous forcez des conscrits à rejoindre la ligne de front parce que vous avez des problèmes d’effectifs », JD Vance ne fait rien d’autre que de dévoiler au monde entier ce qui a été caché pendant trois ans par la propagande de guerre atlantique. Ceci est maintenant présenté au monde – de manière instrumentale et certainement pas pour des raisons éthiques – par le nouveau cours des États-Unis, face à une guerre qui est clairement perdue et qui est maintenant rejetée ouvertement sur la population européenne. Une Europe dont la classe dirigeante, réaffirmant la défense jusqu’au dernier Ukrainien avec la rhétorique de la « paix juste », annonce avec un patriotisme démocratique des plans ignobles de réarmement et de dissuasion nucléaire.

La guerre est le terrible horizon historique de notre époque.

En Suède et en Norvège, des brochures sont distribuées et des cimetières sont agrandis pour préparer la population à l’éventualité d’une guerre avec la Russie ; Von der Leyen déclare qu’elle veut « la paix par la force » ; Macron propose d’étendre la force de frappe française à l’Europe ; en Lombardie, on prévoit l’augmentation des stocks d’iode en cas d’attaque nucléaire ; l’OTAN encourage la mobilisation de la société civile des pays alliés de l’Indo-Pacifique pour préparer un conflit avec la Chine ; l’armée italienne se prépare à enrôler quarante mille soldats supplémentaires.

Dans un cadre d’interdépendance technologique et financière entre la Chine et les États-Unis, l’élection de Trump met en lumière l’affrontement qui oppose depuis des années les factions globaliste et souverainiste des classes dirigeantes occidentales. Pour résumer, la première vise à une confrontation directe et à tout prix avec la Russie, la seconde est favorable à un accord avec le Kremlin pour viser, d’ici quelques années, directement la Chine; mais toutes deux convergent vers un point précis : le réarmement européen (d’ailleurs décidé et annoncé bien avant le retour du roi Donald). Un jeu de miroirs et de provocations qui, s’il peut aboutir d’un jour à l’autre à l’anéantissement nucléaire de l’ensemble de l’humanité, fera de l’Europe, si ce n’est un amas de décombres radioactifs, une forteresse blindée et militarisée, dominée par une économie de guerre qui absorbera toutes les ressources et énergies sociales.

La guerre de notre siècle est hybride, totale, asymétrique, civile. Son champ de bataille est partout.

La guerre du XXIe siècle est une guerre sans limites, qui prend des formes variées et généralisées. Elle se déroule dans les flux d’énergie, prend la forme d’attaques et de sabotages d’Etat, intègre pleinement l’argent, les médias et les réseaux sociaux. La centralité prise par la technologie et le développement scientifique se répercute dans tous les domaines de la guerre, à travers les drones, les applications impliquant la population dans les services de intelligence (par exemple pour signaler les positions des unités ennemies), ou encore avec la révolution de l’intelligence artificielle dans les doctrines militaires, qui a un poids et des conséquences comparables à l’invention du nucléaire. Si l’IA et les technologies numériques sont fondamentales pour faire la guerre, la recherche de la primauté sur ces dispositifs alimente la compétition à l’échelle internationale pour le pillage des matières premières et le vampirisme énergétique. Les hypothèses de « dissuasion bactériologique » et la valeur ouvertement militaire des bio-laboratoires font coïncider guerre militaire et guerre au vivant.

Cela ne veut pas dire que les formes « traditionnelles » et sanglantes de la guerre disparaissent. Au contraire, elles réapparaissent sur les fronts d’une guerre mondiale qui peut être « fragmentaire » pour le moment, mais qui émerge de plus en plus clairement comme produit de la crise de l’hégémonie mondiale des États-Unis et de la confrontation avec ses adversaires, en particulier la Chine. Sur le front ukrainien, la conscription massive et la guerre de position nous rappellent ce qui s’est passé pendant la Première Guerre mondiale. Sur le front du Moyen-Orient, où l’appui des États-Unis au colonialisme de peuplement israélien – qui est né comme avant-poste des intérêts occidentaux – signifie qu’ils tentent de préserver leur domination sur la région, le génocide sioniste à Gaza et en Cisjordanie ramène à notre époque ce qui s’est passé pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Il ne s’agit cependant d’un retour du XXe siècle, mais plutôt de l’alimentation réciproque du progrès technique et de la mobilisation générale dans la guerre totale du XXIe siècle.

Le développement de la technique est aujourd’hui l’horizon central des forces qui se disputent la domination du monde.

Avec un renversement entre le concept de moyen et de fin, la technique axée sur la science moderne s’affirme selon sa propre logique. Le rôle du système satellitaire Starlink d’Elon Musk – qui s’est imposé dans la guerre en Ukraine – donne la mesure d’un protagonisme sans précédent des multinationales de la haute technologie, mais, comme dans d’autres phases de la révolution industrielle, le rôle de l’État ne disparait pas. Au contraire, il assume même une centralité renouvelée. Ce n’est pas par hasard que le projet Stargate de la nouvelle administration américaine – 500 milliards pour le développement de l’IA – a été comparé au projet Manhattan, celui qui a conduit aux bombardements atomiques d’Hiroshima et de Nagasaki.

La nature automatisée du génocide à Gaza semble être l’expérimentation sur les « sauvages des colonies » de ce qui est susceptible d’arriver aux civilisés eux-mêmes, de la même manière que le génocide des Hereros en Namibie par le colonialisme allemand (et l’ensemble des génocides commis par d’autres puissances coloniales) a précédé et préparé l’activité des camps d’extermination pendant le nazisme. Et alors qu’il devient de plus en plus clair qu’il existe dans l’organisation du monde-guerre un surplus d’humanité dont on peut se passer et qu’il faut gérer ou éliminer, l’idée que l’on peut se passer de l‘humanité en tant que telle (comme le prônent ouvertement certains courants technocratiques qui sont proches des salles de contrôle) est en train de s’affirmer.

La guerre est avant tout un fait de politique intérieure – et le plus odieux de tous.

C’est ainsi que Simone Weil, âgée de 24 ans, mettait en garde dans ses Réflexions sur la guerre (1933) contre l’erreur de considérer la guerre comme un fait de politique étrangère. Si les événements dramatiques auxquels nous assistons chaque jour en live streaming risquent de nous paraître lointains, la guerre est plus proche que nous ne l’espérons inconsciemment.

À notre coté se trouvent ses nombreuses bases matérielles – des centres de décision aux usines d’armes et de munitions, en passant par les hubs logistiques qui font partie intégrante de la logistique militaire et un système universitaire qui sert de laboratoire à l’industrie de guerre -, de plus en plus nourries par des plans de réarmement massifs. Et dans le monde des données et de la numérisation, les frontières entre civil et militaire ne cessent d’être franchies dans les deux sens : une application qui sert aujourd’hui à nous profiler en tant que consommateurs, patients ou « citoyens numériques », peut servir, ailleurs comme ici, à bannir, enrôler ou éliminer une partie de l’humanité considérée comme ennemie ou inutile, tandis que les données que nous produisons chaque jour sont directement au service de la surveillance et des armées.

S’il est vrai que la guerre commence ici, il est tout aussi vrai qu’elle y revient. Elle y revient en tant que nécessité de « pacifier » l’arrière-garde, en le militarisant : l’expérimentation des « zones rouges » après la Saint-Sylvestre, la tentative de promulguer un code de loi martiale avec le Paquet Sécurité (également signé par le ministre de la Défense), l’extension du « modèle Caivano » à d’autres banlieues. Sur le plan intérieur, les conséquences en cascade du conflit entre les États qui payent les classes subalternes sont nombreuses – augmentation des factures, aggravation de la précarité, fin de ce qui reste de l’État dit « social » – justifiées par la nécessité du réarmement et de la défense nationale et européenne, avec le recours constant à l’urgence et à sa militarisation. C’est ce que nous avons largement vécu pendant la « période pandémique », où la guerre contre le virus a préparé la guerre actuelle avec l’expérimentation à grande échelle de la mobilisation générale.

La guerre totale est en même temps une guerre civile mondiale.

Les conditions de cette guerre civile sont largement manifestes à nos latitudes aussi, comme plus d’un l’a déjà dit au siècle dernier. La rupture des liens idéologiques, le conflit interne à l’État et même aux classes éclatées, est le symptôme que la barbarie n’est pas lointaine, mais qu’elle se déploie aussi à l’intérieur des murs érigés par la « civilisation » et le « progrès ». Il suffit de penser à ce qui se passe dans les banlieues en tant que reflet de la « guerre entre les pauvres » – Italiens contre étrangers, chômeurs contre travailleurs au noir, petits commerçants contre les non-autorisés, réguliers contre illégaux, habitants des HLM contre squatters, citoyens contre Roms, antagonistes contre « maranza »… Si nous nous rendons ensuite au Royaume-Uni, nous constatons le retour des pogroms (avec des migrants et des islamiques au lieu de juifs et de Roms). Si les insurrections et les révolutions modernes sont toujours des guerres civiles, les deux termes ne coïncident pas. Aujourd’hui, on est précisément en présence d’une guerre civile ubiquitaire et horizontale, en l’absence d’une guerre sociale.

Il arrive cependant que le conflit s’exprime verticalement, comme dans les émeutes de George Floyd et puis, avec une composition socialement inversée, dans la prise d’assaut à Capitol Hill (USA, 2020 et 2021 : d’abord des prolétaires de toutes couleurs contre les patrons et les institutions, et en particulier contre la police ; ensuite un mélange de classes, mais généralement plébéiennes et blanches, contre l’élection de Biden) ; dans les affrontements des peuples indigènes contre le marco temporal de l’agro-industrie (Brésil, 2023) ; dans les émeutes des banlieues françaises (de 2005 aux plus récentes « émeutes de Nahel ») et, à nos latitudes, dans les vives manifestations anti-policières après l’assassinat de Ramy Elgaml à Milan par des carabinieri.

Les phénomènes de désintégration sociale représentent en tout cas une menace pour l’ordre établi, à laquelle l’Etat répond de manière autoritaire, de façon totalement transversale aux taxonomies formelles de gouvernement (démocratie vs. autocratie), sans médiations autres que celles offertes par le progrès technique. Il suffit de penser à la numérisation et à la biométrisation des identités légales, par lesquelles l’identité civile devient indiscernable d’un dispositif de surveillance automatisé. Aujourd’hui, le « citoyen » qui se révolte ou n’obéit pas est de plus en plus mécaniquement mis « hors-la-loi ».

Reconnaître la tendance à la guerre n’est pas accepter son caractère inéluctable.

Si la religion de l’inéluctabilité est le moteur de notre époque, certains signes semblent l’ébranler. En Ukraine, après l’exploit nationaliste, le soutien à la guerre a fait place à des formes de insoumission, de désertion et de non-collaboration massive qui pèsent lourdement sur le sort de ce conflit et laissent entrevoir un possible effondrement du front occidental. Entre-temps, le génocide de Gaza a alimenté un vaste mouvement mondial qui, grâce à quelques minorités obstinées, a redécouvert des formes d’action directe et a amené l’intifada dans les campus américains, se chargeant de dire le non-dit, c’est-à-dire les fondements bellicistes et génocidaires du capitalisme occidental. L’extension de la guerre à toutes les sphères de la société multiplie les occasions de mutinerie et de sabotage, offrant à la variable humaine des possibilités inédites de gripper la machine à tuer.

En revanche, la propagande de guerre a paradoxalement eu prise sur une minorité de la minorité antagoniste, qui est allée jusqu’à exprimer son soutien à une résistance ukrainienne autoproclamée et inexistante, tout en hésitant à soutenir la résistance palestinienne. En montrant une incapacité totale à faire la distinction entre une vague nationaliste fomentée et armée par l’OTAN (et avec de véritables nazis au premier rang, y compris le parlement, les escadrons de la mort, l’armée, la police, la garde nationale) et une résistance anticoloniale contre un des colonialisme de peuplement encore en cours. Si les socialistes parlementaires d’antan ont voté pour les crédits de guerre, leurs héritiers « progressistes » ridicules et corrompus, après un siècle de collaborationnisme de classe, soutiennent le plan de réarmement « ReArm Europe » et appellent à des manif bellicistes « pour la liberté », visant uniquement à soutenir la poursuite du massacre en cours en Ukraine.

Cent dix ans après l’entrée en guerre de l’Italie lors du premier massacre mondial et quatre-vingts ans après la fin de la seconde sur le sol européen, c’est l’histoire de l’antimilitarisme révolutionnaire et, plus encore, celle de ceux qui l’ont abandonné, embrassant la cause de la « guerre juste » du moment, qui éclairent tragiquement la voie à suivre. La seule façon d’échapper aux guerres fratricides est d’assumer la logique du défaitisme et ses implications, c’est-à-dire de travailler à la chute du camp capitaliste qui veut t’enrôler, et la seule façon pour ne pas être enrôlé par le camp capitaliste adverse est la logique de l’internationalisme : la logique par laquelle chaque exploité voit son ennemi dans propre patron, tout en solidarisant avec ses frères et sœurs de l’autre côté du front.

—

C’est avec cette vision du monde qu’est né le projet disfare (Défaire), un bulletin périodique consacré d’une part à l’examen de questions cruciales pour interpréter l’horizon sombre dans lequel nous agissons, et d’autre part à la diffusion de textes contre la guerre totale, pour la plupart inédits en italien, provenant des différents fronts et arrière-fronts du monde, mais aussi du passé.

Le bulletin sera publié en quatre numéros annuels, un rythme très lent comparé à la vitesse vertigineuse de l’actualité, mais qui nous semble – en plus d’être compatible avec nos énergies – adapté à la cristallisation d’une pensée qui tente de s’aventurer au-delà de la surface. Nous nous appuyons sur un instrument papier, sans exclure qu’il puisse être rejoint par d’autres moyens, convaincus que dans la dimension numérique tout passe et rien ou presque ne s’installe, bruit de fond qui n’est pas plus important qu’un autre bruit.

Face à l’accélération des événements de portée historique que nous vivons actuellement, il nous semble utile de nous doter d’une publication qui puisse offrir un espace de discussion et dans laquelle des expériences de lutte et d’analyse, même éloignées géographiquement et peut-être en contradiction les unes avec les autres, puissent dialoguer, avec le désir que cela puisse stimuler la pensée et l’action. C’est pourquoi nous invitons ceux qui nous lisent à contribuer par des textes, des graphiques, des suggestions, des critiques, de la diffusion. Dans l’espoir que l’accélération de ces temps sombres ne nous prenne pas au dépourvu.